ETA Carina. (10h 45m 03.591s / −59° 41′ 04.26″)

It is believed that before Western Sailors ventured south enough to see Eta Carina, once called Eta Argus, that is was the brightest star in the sky as seen from Earth, perhaps as bright as magnitude -4.3, however, since it was discovered by Western astronomers and previously by sailors, it was not this bright, it sat at around magnitude +4.2 right up until the 1830’s.

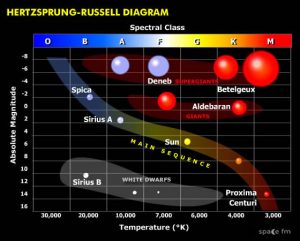

Western Astronomers had not paid much attention to this not overly bright and seemingly average star, little did they know that this is one of our galaxy’s true giants, a type we now call a Galactic Hypergiant.

This all changed in the spring of 1837 when this apparently unassuming average star underwent a massive brightening event that saw it rival mighty Rigel (β Orionis ) and may have actually achieved a visual brightness of -1.5 for a very short period. This was the start of a period now called “The Great Eruption” and it saw the star rise to become the second brightest star in the entire sky in <arch 1843, before it had faded back below naked eye visibility by 1856.

This peeked interest in the star, so it was keenly observed by a number of astronomers of the day. In 1892 it had another smaller eruption, rising to the 6th magnitude before it once again faded.

Astronomers proposed a number for idea for the outbursts, although they knew too little about the inner working of stars to have an credible theories.

Sometime in the 1940’s Eta Carina began to increase in brightness again, when it actually happened in unsure, there was a war on you know, but since then it has steadily rose in brightness to its current magnitude 4.5.

So what is going on?

That is a very good question that has been asked consistently since the late 1830’s. Today we have a distinct advantage over our long lost forbears, not only do we have truly colossal telescopes compared to them, we have orbital missions that can probe the star in everything from gamma rays through UV, visible light, IR and even microwave, and what have we learnt in all that time…?

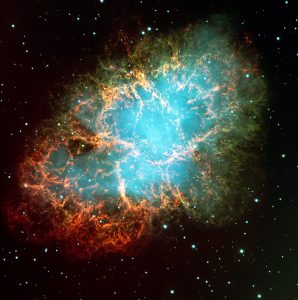

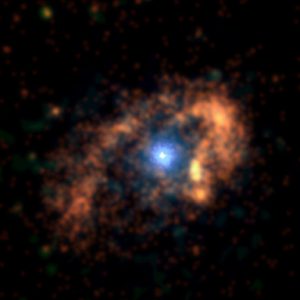

Eta Carina is embedded in a twin area of nebulosity know as The Humunculus and the Little Humunculus. the former caused by the eruption in 1837-1843 and the latter most likely resulting from the outburst in 1892.

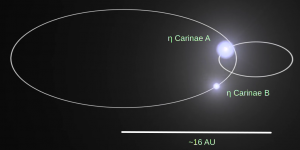

Eta Carina is a member of Trumpler 16 (Tr16), a massive OII star formation region some 7500ly from Earth, Eta Carina is in fact a double star system, consisting of two true giants, Eta Carina A is a colossal 100 times the mass of the Sun, whereas Eta Carina B is estimated to have a mass in the range of 30-80 times the mass of the Sun, no slouch in it’s own right.

Eta Carina B appears to be in a 5.54 year orbit of the primary based on modern observation which show in increase in X-ray emissions every 5.54 years, it may indicate that the star is passing through the extended outer envelope of Eta Carina A. See the images for a theoretical orbit of the pair.

Now, studying light from the outburst that rebounded, or “echoed,” off interstellar dust that has only recently reached Earth, researchers have found the original explosion created an astounding ~12 solar mass cloud of debris expanding more than 20 times faster than anyone ever expected, some 8890 km/s, or more than 32 million km/hr. That is fast enough to cross our entire solar system in a matter of days.

So far, velocities that high have only been seen in the aftermath of supernova explosions, not in events that leave a star intact, not even the smaller Nova eruptions of stars see velocities that high.

So did Eta Carina actually undergo a Supernova event in 1837? Clearly the answer is appears to be NO because the stars are still there, so what is happening?

“We see these really high velocities in a star that seems to have had a powerful explosion, but somehow the star survived,” said Nathan Smith of the University of Arizona. “The easiest way to do this is with a shock wave that exits the star and accelerates material to very high speeds.”

Smith and Rest, of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, wrote a pair of papers in The Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society describing the recent observations and offering a possible explanation.

Researchers first detected the light echoes from Eta Carina back in 2003, using telescopes at the Cerro Tololo Observatory in Chile. Later they secured observing time on the larger Magellan telescopes and Gemini South Observatory, also in Chile, the team collected spectra to allow them to determine the velocity of the expanding debris.. the data they collected simply did not fit with accepted ideas about stellar evolution.

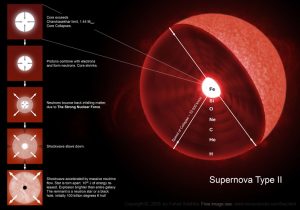

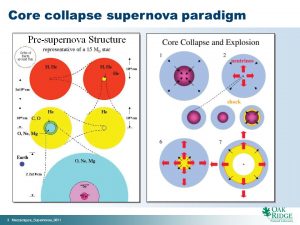

As we have discussed in earlier posts, massive stars normally die when their cores run out of fuel so the outward pressure of fusion generated energy suddenly stops, gravity takes over and we see a core collapses, resulting in the tremendous shock wave that blows the outer layers of the star into space. Current theory holds that, depending on the mass of the progenitor star, it either creates a neutron star, or possibly a stellar mass black hole..

In the case of Eta Carina’s eruption, an unknown process must have produced event that resulted in supernova like shockwave, but came it must have been short of enough energy needed to destroy the star.

What might have happened?

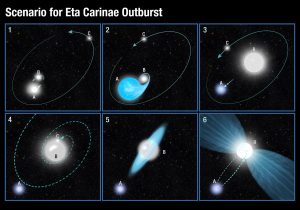

Smith and Armin posit that Eta Carina may have been a triple star system with two massive stars orbiting close together as a binary system with the third star, possibly a few solar masses, orbiting the binary pair.

As the more massive of the binary pair aged, it expanded, filled it’s Roche Lobe and started to exchange it’s outer layers with the other star within the binary.

This second star took a huge amount from the expanded giant, swelling to around 100 times the mass of the Sun, in the process it striped away the dying star’s outer atmosphere, thus leaving an exposed helium core estimated to be around 30 times more massive than the Sun.

“From stellar evolution, there’s a pretty firm understanding that more massive stars live their lives more quickly and less massive stars have longer lifetimes, So the hot companion star seems to be further along in its evolution, even though it is now a much less massive star than the one it is orbiting. That doesn’t make sense without a transfer of mass.” Rest, 2015 Interview.

The transfer of mass from one star to the other would dramatically alter the gravitational balance and architecture of this unusual stellar system, allowing the helium core star to move away from its younger, but now significantly larger, partner, so far, in fact, that gravitational perturbations with the proposed Eta Carina C caused it to spiral inwards toward the binary pair.

The fate of Eta Carina C was sealed, nothing could stop the inevitable collision with the now supermassive star at the heart of the system, resulting in an explosion of gargantuan proportions, reminiscent of a Type II supernova.

In its initial stages, ejected material would have moved relatively slowly as the stars spiralled closer and closer together. When the they finally merged, debris was blown away more than 100 times faster than previous ejecta, catching up and ramming into the slower moving material, generating the colossal output seen ion the 1837-1843 eruption.

The helium-core star, meanwhile, ended up in a short period elliptical orbit that carries it through the giant central star’s outer atmosphere every 5.4 years, generating X-rays and shock waves.

The now binary system shines more than 5 million times brighter than out Sun, inside the massive ejection cloud we see as the Humunculus nebula.

The Future

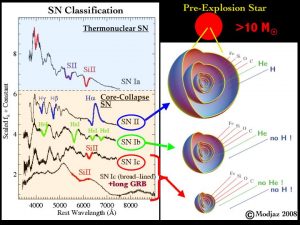

The future of both stars is sealed, both are so massive that both will end their lives as Supernova. Eta Carina B is now the less massive star, but it is highly evolved, the helium shell is undoubtedly burning heavier elements beneath it’s layers, so when this will erupt as a type Ia supernova is pure speculation.

Eta Carina A is doomed, as a Galactic Hypergiant it now has no escape route to it’s ultimate fate, as it burns hydrogen as a prodigious rate the core will fill up with helium ash, the star will expand to even more colossal proportions, will it also absorb it’s older family member, who knows, but at an average orbital separation of around 15.5 AU (2,320,000,000km), or about half way between Saturn and Uranus in our Solar system, there is good reason to think that it too will be absorbed as it already appears to pass through the outer atmosphere already, perhaps this is already the start of it’s death dive.

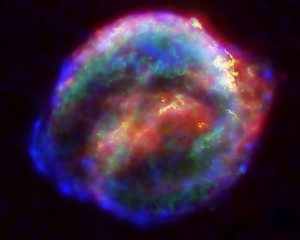

Of course any star around naked eye visibility erupting as a supernova would be a pot of gold for researchers and amateurs alike. Not only would it be a spectacular visual site, but information gleaned from such a nearby event would be, literally, astronomical. The fact that such a huge star would be the culprit would make it even more special, not only would we learn a huge amount about the immediate events following such a core collapse event close up, but we would get valuable information about how such an event would impact the other star in this binary system and the massive nebula already surrounding this binary pair.

Just an end note, the absolute magnitude of Eta Carina is -8.6, to put that in perspective, Venus at it’s closest can reach -4.4 magnitude and the full Moon is magnitude -12.7. This would make Eta Carina some 80 times brighter than Venus is it were only 32.6 light years away, what a spectacle that would be.