Introduction

There is a Youtube video by Anton Petrov at the end of this article ( I have also added a couple of his other videos on other discoveries about simple organisms) with an important update on how some simple organisms are rewqriting what we thought we knew and giving clues as to how cells, as we know them, came about. I would urge all who read this to watch the video – Fascinating.

Abiogenesis, the origin of life from non-living matter, is a profound unsolved problem in science. Life emerged on Earth at least 3.5 billion years ago, the age of the earliest undisputed microfossils, and likely even earlier (before the Late Heavy Bombardment ~3.9 Ga). This suggests a relatively rapid appearance of life once conditions became hospitable. Yet the precise sequence of events from simple chemistry to the first cells remains unknown, partly because early biological traces have been largely erased by billions of years of geological activity (Link). Understanding abiogenesis is significant not only for explaining our own origins, but also for estimating how likely life might be elsewhere in the universe. The very rapid rise of life on early Earth has led some to speculate that given the right conditions, life’s emergence could be “reasonably likely” over tens of millions of years (Link). Others caution it may have been an extraordinarily improbable event – a singular fluke that just happened to occur in Earth’s primordial environment (Link). In either case, uncovering how inanimate molecules transitioned into living systems would illuminate the fundamental principles underlying biology.

Modern origin-of-life research spans multiple disciplines and perspectives. There is consensus that life’s origin was a gradual process involving many steps: simple molecules had to form larger organic compounds (using elements like C, H, N, O, P, S) and assemble into systems exhibiting protometabolic, compartmentalisation, and inheritance (Link). Beyond this broad outline, however, theories diverge. Competing models emphasize different “starting points” for life – for example, a primordial self-replicating RNA (“RNA world”) vs. networks of chemical reactions (“metabolism-first”). For decades these views were seen as mutually exclusive, but recent research often aims to bridge them, recognizing that multiple aspects (genetic molecules, catalysts, membranes, energy sources) had to co-evolve. Over the past ten years, significant progress has been made both experimentally and theoretically in probing these steps. Scientists have simulated plausible early Earth conditions in the lab, discovering new pathways to essential biomolecules and even rudimentary “protocells.” They have also applied computational and comparative genomic methods to infer features of the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA), providing clues about life’s earliest metabolic and genetic systems. This report reviews the latest developments (circa 2015–2025) in abiogenesis research, focusing on how simple molecules might have transitioned into protocells – the precursors of true cells. We first summarize key theoretical models (RNA world, metabolism-first, lipid world, and hydrothermal-vent hypotheses) and then examine supporting evidence from experiments and planetary observations. Next, we discuss how these components could come together in protocells and evolve toward LUCA. Finally, we highlight ongoing challenges and open questions and consider future directions in this interdisciplinary field.

Key Theoretical Models

RNA World Hypothesis

One of the most prominent theories for life’s origin is the RNA World hypothesis. It proposes that early life was centred on self-replicating RNA molecules that both carried genetic information and catalysed chemical reactions (Link). In this scenario, RNA arose before DNA and proteins, acting as a one-molecule system for heredity and metabolism. The rationale is that RNA can fold into enzyme-like catalysts (ribozymes) and also store information in its nucleotide sequence. If a supply of RNA’s building blocks (nucleotides) existed on the prebiotic Earth, they could polymerize into RNA strands, setting the stage for Darwinian evolution: any RNA sequence that could help make copies of itself (for example by catalysing nucleotide addition) would gain a selective advantage. Over time, an “RNA world” of replicating RNAs could develop greater complexity. Eventually, this RNA-based system is thought to have given rise to protein enzymes and DNA genomes, but RNA’s central role in modern cells (e.g. ribosomal RNA catalysing protein synthesis) is seen as an evolutionary echo of this early stage.

In the last decade, researchers have made notable advances addressing how an RNA World could get started. A major challenge had been explaining the prebiotic origin of RNA’s nucleotides (adenine, guanine, cytosine, uracil + ribose sugar and phosphate), which are complex and unlikely to form spontaneously all at once. Recent breakthroughs in prebiotic chemistry have shown plausible pathways to these building blocks under early Earth conditions. For example, in 2009, John Sutherland’s team found an ingenious route to generate activated pyrimidine nucleotides (cytosine and uracil) from simple precursors like cyanamide, cyanoacetylene, phosphate, and glyceraldehyde in water (Link). This solved a “near miracle” problem of how RNA subunits might assemble spontaneously. Further work in 2015 demonstrated that just two simple starting compounds (cyanide and acetylene derivatives, with phosphate) can drive a network of reactions yielding not only nucleic acids, but also amino acids and lipid precursors (Link). In other words, a unified chemistry might produce the three major classes of biomolecules in tandem – a finding hailed as “very important”. By 2016–2018, researchers had also synthesized purine bases (adenine, guanine) via prebiotic routes, completing the set of the four RNA bases. These advances lend credence to the idea that the early Earth’s chemical environment could furnish the raw ingredients for an RNA world.

Another hurdle is that RNA is a relatively fragile molecule, and long RNA polymers are hard to form and replicate without enzymes. Yet progress has been made here as well. Scientists have evolved RNA molecules in the lab that can catalyse RNA polymerisation – effectively RNA enzymes that copy other RNAs. For instance, improved versions of the “RNA polymerase ribozyme” can now synthesize RNA strands hundreds of nucleotides long (though still not long enough to fully replicate themselves) (Link). Such ribozymes demonstrate the feasibility of RNA self-replication in principle, even if the very first replicator has not been recreated. The discovery of natural ribozymes (like self-splicing introns and the ribosome’s peptidyl transferase centre) already showed that RNA can have diverse catalytic functions. The newer polymerase ribozymes, with increasing efficiency, suggest that an RNA-based replication cycle could emerge under the right conditions. Still, the RNA World hypothesis faces open questions: How could the first RNAs form amid a messy prebiotic soup without enzymes? How were concentrations of nucleotides achieved, and how was the problem of chirality (all biological nucleotides being one mirror form) resolved? These questions motivate ongoing research, but overall the past decade’s findings significantly strengthen the case for an RNA-centric origin of life. RNA provides a clear mechanism for inheritance and evolution, and we now have experimentally supported pathways for its synthesis (Link). The RNA World hypothesis thus remains a central (if evolving) framework for thinking about abiogenesis.

Metabolism-First Theories

In contrast to gene-first scenarios like the RNA World, metabolism-first theories posit that life began as self-sustaining chemical reaction networks, primitive metabolic cycles, before genetic molecules appeared. The idea is that a web of reactions could gradually become more complex and self-organised, laying a chemical foundation that informational polymers later exploited. One classic metabolism-first model is Wächtershäuser’s “iron–sulphur world,” which envisions early metabolism on mineral surfaces (such as Iron pyrite, (FeS₂)) near hydrothermal vents. In such environments, abundant inorganic catalysts (transition metal sulphides, etc.) and a continuous energy source could drive formation of organic molecules. Key biochemical reactions, for example, fixation of carbon dioxide into molecules like acetate (C2H3O2-), might have been running on the early Earth as geochemical processes, before any enzymes or nucleic acids existed. These reactions could form a primitive protometabolic, producing building blocks (like small carbon compounds) that later fuelled the emergence of nucleic acids and proteins.

Recent research lends some support to metabolism-first notions by showing that several core metabolic reactions can occur non-enzymatically with simple catalysts. A striking example was provided by Markus Ralser and colleagues, who demonstrated that parts of central metabolism can be mimicked by just metal ions and phosphate in solution. In 2014, they reported a series of reactions analogous to glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway – normally enzyme-driven pathways that break down sugars – proceeding in the presence of Fe²⁺ ions, phosphate, and other small molecules. These metal-catalysed reactions produced some of the same sugar intermediates and biomolecules as modern metabolism, but without proteins, suggesting that simple catalysts on the prebiotic Earth (perhaps in mineral-rich sediments) could have supplied critical biochemicals. The implication is that an “organic chemistry engine” might have been running before life, powered by mineral surfaces and inorganic catalysts. Over time, nascent biomolecules like peptides or RNA could have integrated into this network, eventually taking over catalysis from the raw environment. Indeed, Ralser et al. propose an attractive hypothesis for how the first enzymes arose: small RNAs or peptides that bound metal ions (like Fe²⁺) would concentrate and localize those catalytic metals, making the chemical reactions more efficient. Those rudimentary catalysts could then evolve specificity, becoming the protein enzymes and ribozymes we know, but initially they were simply improving pre-existing chemistry.

Other metabolism-first ideas invoke autocatalytic sets of molecules, where the output of one reaction serves as the input for another in a closed loop, so the network as a whole is self-sustaining. Pioneers like Stuart Kauffman theorized that if a sufficiently diverse mixture of organic molecules existed, some subset might form a self-replenishing catalytic cycle by chance. Experimental evidence for fully autocatalytic networks remains limited, but there are hints (e.g. the formose reaction, discovered in 1861, where formaldehyde spontaneously yields sugars via autocatalysis. In recent years, chemists have constructed small synthetic networks that exhibit network autocatalysis (for example, replicating peptide networks), though these are still far simpler than a true metabolism. The metabolism-first view receives indirect support from the reconstruction of LUCA’s metabolism (discussed later), which appears to have been autotrophic and mineral-based. If life’s last universal ancestor metabolised hydrogen and CO₂ with the help of metal cofactors, it suggests life’s origin was tied to geochemical energy flows. Metabolism-first theories, however, face the challenge of generating information and heredity – a metabolic cycle might persist, but how would it improve or complexify without genetic instructions?

Proponents argue that chemical systems could undergo a form of natural selection if they compete for limited substrates or catalysts. Still, the lack of a clear mechanism for information storage is a criticism. Current research is increasingly trying to merge replicator-first and metabolism-first: perhaps molecular replication (like RNA) began within the confines of a supportive metabolic environment, meaning the earliest life was a hybrid of both approaches. Overall, metabolism-first theories highlight the importance of environmental factors (minerals, energy gradients) and suggest that life’s emergence was chemically incremental – “genetic takeover” of a pre-existing chemical engine, rather than genetics from scratch.

Lipid World Hypothesis

A third perspective, sometimes viewed as a variant of metabolism-first, is the Lipid World hypothesis. This idea centres on the role of amphiphilic molecules – the kind that form membranes – in the origin of life. The Lipid World posits that life began with self-organizing assemblies of lipids (fatty acids or other amphiphiles) that formed micelles and vesicles in the primitive oceans (Link). These membranous compartments, it is argued, could undergo a form of selection and evolution based on their stability, growth, and division, even before the advent of genetic polymers. In other words, the first “protocells” might have been lipid bubbles that could grow (by incorporating more lipid), replicate by budding or splitting, and even compete, without any nucleic acids inside. Supporters of this hypothesis note that membranous vesicles can indeed form spontaneously under prebiotic conditions – fatty acids (which could be produced by abiotic chemistry or delivered by meteorites) will assemble into bilayer vesicles given the right pH and salt conditions. Such vesicles encapsulate whatever molecules are in solution, creating distinct internal environments.

Compartmentalisation itself is thought to be a crucial step in abiogenesis, because it localises reactions and maintains concentrations of reagents. The Lipid World takes this further by suggesting the compartments came first and provided a testbed for chemical evolution. The “information” in a lipid world would be compositional rather than genetic – i.e. the specific mixture of lipids (and other trapped chemicals) in a vesicle could affect its properties and persistence, and those features could be inherited (approximately) by progeny vesicles if they split. Over many cycles, vesicle populations might “evolve” greater stability or catalytic capability (for instance, if certain lipids also have catalytic surfaces).

A key question for the Lipid World is how it eventually gave rise to template-based genetics (RNA/DNA). Recent work has started to address this by outlining scenarios in which lipid vesicles and polymers co-evolve. One novel proposal (Subbotin & Fiksel 2023) suggests that Darwinian evolution could initially occur among liposomes alone, driven by environmental cycles. In their model, day–night temperature cycles and gravity cause a selection process: during the day, fatty-acid vesicles form near the surface and encapsulate “heavy” solutes; at night, these loaded vesicles sink (protecting them from UV radiation) and persist longer. The longer-lived vesicles have more time to undergo autocatalytic lipid replication (some amphiphiles can catalyse the formation of more membrane molecules), and those that grow and divide successfully pass on their compositional traits. Through this mechanism, a population of vesicles could acquire adaptations (e.g. mixtures of lipids that confer stability or efficient growth), essentially, a primitive form of heredity and selection at the protocell level. Only later, after a robust population of protocells exists, would the “accidental” incorporation of RNA precursors lead to the emergence of true genetic molecules inside some vesicles. Those hybrid protocells (with both membrane and genes) would have a huge evolutionary advantage, eventually dominating and leading to an RNA–lipid world and then to modern cells. This scenario is speculative, but it tries to solve one of the Lipid World’s criticisms – the lack of a genetic apparatus. It shows a path by which information (as encapsulated chemical content and lipid composition) could be handled by vesicles, buying time for RNA to appear after a basic evolutionary process was already underway.

Support for the Lipid World also comes from lab experiments on protocell dynamics. Researchers have observed that simple vesicles can grow, divide, and reproduce in surprising ways. For example, providing fatty acid “food” to model protocells causes them to enlarge and eventually split into daughter vesicles without any complex machinery – a physical process of membrane instability that yields proliferation. Different amphiphiles can impart different properties: mixed fatty-acid chains yield more robust membranes than single-chain types, and the presence of certain oils or salts can stabilize vesicles under a wider range of conditions (phys.org). One long-standing challenge had been that fatty acid membranes are unstable in hot, high-salt environments (like the primordial ocean or hydrothermal vents), but recent experiments showed that using mixtures of lipids of various lengths (and including fatty alcohols) produces vesicles that thrive in warm, alkaline, salty water (phys.org). In fact, heat and alkalinity can promote vesicle formation when the lipid composition is diverse (phys.org). This finding, published in 2019, is important because it suggests membranous protocells could form in realistic early Earth settings (not just in ideal lab conditions). It also links the Lipid World idea to the vent hypothesis (coming next), since it implies membranes wouldn’t necessarily fall apart at higher temperatures or extreme pH. The lipid world hypothesis remains a compelling piece of the puzzle, it emphasises the importance of compartmentalisation first, that without cells (even simple ones), replicators and metabolic reactions might never achieve the complexity needed for life. By demonstrating that evolution can begin at the level of whole compartments, this model provides a bridge between pure chemistry and the highly organised structure of a cell.

Hydrothermal Vent Hypothesis

The hydrothermal vent hypothesis proposes that life’s origin took place in and around submarine hot springs on the ocean floor. In particular, alkaline hydrothermal vents – like those of the modern “Lost City” hydrothermal field in the Atlantic – have been highlighted as especially favourable cradles of life. These vents form where warm, hydrogen-rich fluids from below the seafloor mix with cooler, carbon dioxide–rich ocean water, creating steep chemical and pH gradients. The result is a porous, rocky structure (chimneys and foam-like mineral labyrinths) with alkaline (high pH) interiors and relatively acidic seawater exteriors (phys.org). Such vents produce a natural proton gradient (a difference in hydrogen ion concentration) across their mineral walls, essentially acting as a geological “battery.” This is intriguing because all living cells power their metabolism using proton gradients across membranes (chemiosmosis).

Vent proponents argue that life’s metabolism essentially borrowed the existing proton-motive force in these vents before cells had evolved to generate it on their own. In addition, vents supply abundant chemical energy: hot fluids often contain H₂ (hydrogen gas), which can react with CO₂ (catalysed by transition-metal minerals) to form organic molecules(phys.org). This is analogous to the Wood–Ljungdahl (acetyl-CoA) pathway found in some modern microbes, which uses H₂ to fix CO₂ into acetate – notably, one of the most ancient metabolic pathways.

Indeed, geochemists have shown that under vent-like conditions, H₂ and CO₂ can be converted into simple organics like formate, acetate, and pyruvate with the help of minerals such as iron sulphide and nickel sulphide (laboratory simulations have achieved steps of this chemistry). Thus, an alkaline vent could have been a steady factory of basic building blocks, fuelling a proto metabolism in its nooks and crannies.

Another advantage of hydrothermal vents is compartmentalisation. The nano to micro scale pores in vent chimney rock could serve as prebiotic reaction chambers, concentrating molecules that would otherwise be too dilute in the vast ocean. As warm, chemically rich water flows through the porous rock, organic products can build up in the tiny cavities, perhaps forming gel-like phases on the mineral surfaces. Some origin-of-life researchers liken these inorganic compartments to the first “cells,” with the mineral walls playing the role of a semi-permeable membrane. Within such chambers, chemical gradients and catalysts could drive increasingly complex reaction networks, a clear overlap with the metabolism first idea. The vent hypothesis effectively combines metabolism first (geochemical energy, catalysis, and cycles) with compartmentalisation, removing the need for an exposed oceanic “soup.”

Over time, as organic membranes and genetic molecules emerged, these components might have taken over the role of the mineral pores, allowing the first true cells to leave the vent environment. In one vision, protocells could form inside the pores and eventually bud off once they are autonomous, a bit like larvae leaving a nursery.

Recent experimental findings have strengthened the plausibility of vent scenarios. In 2020, a team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory recreated ancient ocean vent conditions in the lab by simulating high-pressure mixes of H₂ rich fluids and CO₂ rich ocean water. They showed that this setup does produce organic molecules, the basic building blocks of life, when the fluids interact with mineral catalysts under heat and pressure (nasa.gov).

Amino acids and other complex organics were detected, demonstrating that vent chemistry can forge biomolecules in situ. Similarly, as mentioned earlier, researchers at UCL (Jordan, Lane, and colleagues, 2019) tested protocell formation in vent-like environments. By using mixed amphiphiles and vent analogue conditions (warm, alkaline, salty water), they achieved the self-assembly of protocell membranes where prior attempts had failed (phys.org). Impressively, heat and high pH – once thought to be hindrances – were actually required for robust vesicle formation when long-chain lipids were present. This suggests that far from being incompatible with membranes, hydrothermal conditions could encourage the formation of the first cells. The authors concluded that deep-sea vents remain a very viable location for life’s origin, and their data “add weight to that theory with solid experimental evidence”. Additionally, geological discoveries provide tantalizing support: fossilized remains of microbial filaments and structures have been reported in ancient hydrothermal deposits dating to 3.77–4.3 billion years ago (phys.org), which, if confirmed as biological, would indicate vent ecosystems existed extremely early. While there is debate about these particular microfossils, their context underscores that hydrothermal systems were present and chemically active on the young Earth, and perhaps life was there as well.

In summary, the hydrothermal vent hypothesis paints a picture of life emerging deep under the sea, harnessing Earth’s internal heat and chemistry. It elegantly accounts for how the earliest life might have gained energy (using natural proton gradients and redox reactions) and how molecules could concentrate and complexify (within rock pores) without preformed enzymes or membranes. This model does assume an aqueous environment – so it stands in contrast to models favoring surface “warm little ponds” with wet–dry cycles (which we have excluded here in favor of the vent emphasis). It’s possible that both played roles at different stages, but many researchers see alkaline vents as one of the most plausible singular locales for abiogenesis. The challenge for vent theories is to demonstrate a continuous path from inorganic chemistry to free-living cells – but as we’ve seen, pieces of that path (metabolic reactions, monomer synthesis, protocell formation) have been experimentally demonstrated under vent-like conditions, especially in the past decade. This convergence of evidence makes the vent hypothesis a leading contender in origin-of-life research.

Experimental Evidence

Building on the theoretical models above, a variety of experiments have attempted to recreate aspects of early Earth chemistry and test the feasibility of different steps in abiogenesis. Here we review key experimental findings from the last ten years that illuminate the path from simple molecules to protocells, as well as relevant observations from planetary science.

Simulating Prebiotic Chemistry

Ever since the classic Miller–Urey experiment in 1953, which produced amino acids from a spark discharge in a mixture of primordial gases, laboratory simulations have been a cornerstone of origin-of-life research. Modern experiments have updated these approaches to reflect current understanding of Earth’s early atmosphere and oceans. (We now think the atmosphere was dominated by CO₂ and N₂, with only small amounts of reducing gases like CH₄ or NH₃.) For example, researchers found that in a CO₂/N₂ atmosphere, electric sparks yield significant amounts of nitrite (NO₂⁻), which rapidly destroys amino acids – implying the original Miller–Urey conditions were probably too reducing compared to reality.(Ref. Link) Nonetheless, organics could still form in localized environments; variations of Miller’s setup with added minerals, UV light, or alternate gas mixtures continue to yield biologically relevant compounds. Recent studies have incorporated substances like silica (SiO₂) or borate minerals into simulation experiments to stabilize certain products (borate can stabilize ribose sugar, for instance). A 2025 study by Jenewein et al. showed that when an atmosphere rich in CO₂/N₂ is simulated with spark discharge in the presence of silicate minerals, an interesting thing happens: a polymeric organic film (from hydrogen cyanide chemistry) coats the surfaces and spontaneously forms cell-like microstructures within it (Ref Link).

These “biomorphic protocells” (spherical vesicle-like forms) appeared at the water–gas interface via bubbling processes (Ref Link). In essence, the experiment simultaneously produced prebiotic organic compounds and membranous compartments. The authors suggest this means early Earth could have generated protocells and molecular building blocks side by side, rather than sequentially, a remarkable result that potentially accelerates the timeline to life.

Such experiments underscore that we must consider complex interactions (atmosphere, ocean, minerals, energy sources) all together, rather than isolating single factors. Conditions on the early Earth were dynamic, with volcanic eruptions, lightning, UV radiation, and meteorite bombardment all contributing energy that drove chemical reactions. By using high-energy lasers to simulate meteoritic impacts, for example, scientists have shown formation of amino acids and nucleobases in shock-heated mixtures, complementing the gentler spark and UV experiments.

From Monomers to Polymers, another experimental focus has been how simple organic monomers (amino acids, nucleotides, etc.) could link into polymers (proteins, nucleic acids) without enzymes. In water, unassisted polymerisation is difficult because hydrolysis competes with condensation. But researchers have discovered plausible ways around this. One mechanism is drying and re-wetting cycles, such as on tidal flats or in geothermal pools, which can concentrate solutes and promote polymer formation during evaporation. Experiments have shown that cyclic drying of amino acid solutions can indeed form peptide chains, and likewise, drying of nucleotide mixtures in the presence of phosphates or clay minerals can yield RNA-like oligomers. Clay minerals (like montmorillonite) have been found to catalyse the assembly of RNA by bringing nucleotides into close proximity on their charged surfaces. In the 2000s, James Ferris and colleagues demonstrated RNA oligomers over 50 units long could form on clay in a lab setup, although yields were low. Recent work has built on this by using mixtures of nucleotide analogues and activating chemicals to achieve non-enzymatic RNA polymerization in simulated prebiotic ponds. For instance, one study combined wet–dry cycling with lipid vesicles, finding that RNA strands could form inside fatty acid compartments during dehydration and remained encapsulated upon rehydration – effectively showing polymerization and encapsulation occurring together (an important synergy).

Key Experiments Supporting Different Models: Each theoretical model discussed earlier has inspired specific experiments. For the RNA World, beyond the monomer synthesis advances already noted (Sutherland’s work(Ref Link)), researchers have sought to demonstrate template copying with simple chemistries. In 2013, scientists showed that nucleotide building blocks could spontaneously assemble into short RNA chains on the surface of basaltic glass (common in early volcanic islands) – a hint that young Earth rocks could have helped make the first RNAs. Another line of work showed that certain cyclic nucleotides (which can form from drying wet nucleotides) will polymerize into RNA all by themselves in water, as was reported in 2017. In the realm of metabolism-first, experiments have tried to create autocatalytic cycles in vitro.

A notable 2019 study managed to get a synthetic network of three reactions to sustain itself (each reaction’s product catalysed the next step, and the final product catalysed the first) – a rudimentary analogue of an autocatalytic set. While far from a full metabolism, it proved that closed-loop chemical systems can form under the right conditions. There’s also been progress in “metals and minerals as catalysts”: in addition to Ralser’s non-enzymatic glycolysis (Ref Link), researchers in 2019 demonstrated that the citric acid cycle (or at least a significant portion of it) can run in the presence of ferrous iron, without enzymes, when supplied with CO₂ and simple acids. This supports the notion that core metabolic cycles could have a prebiotic origin in metal-rich environments.

For the Lipid World, experiments have explored the self-replication of vesicles. One clever demonstration showed that vesicles encapsulating a clay mineral could “reproduce” faster because the clay catalysed lipid formation internally, causing the vesicle to grow from within and eventually split. Another experiment (2018) created vesicles that grow by consuming smaller micelles, mimicking how primitive cells might have absorbed molecules from their environment to expand. Researchers also measured competition between vesicles: vesicles that could steal lipids from others would grow at their expense – a possible primitive selection mechanism. Such experiments illustrate that even without genes, vesicle populations can exhibit dynamics analogous to competition and selection. Meanwhile, those investigating hydrothermal vents have built laboratory apparatus that mimic vent conditions: for example, maintaining a thermal gradient across a porous rock interface, with alkaline solution on one side and acidic on the other.

In 2017, one group reported sustained production of formate and other organics in a setup like this, directly demonstrating the vent chemistry paradigm. Another fascinating experiment from 2022 circulated CO₂-rich water through tiny chambers in a metal hydroxide precipitate (similar to vent chimneys) and showed formation of amino acids and simple peptides – essentially testing if vents could not only make monomers but also begin polymerizing them.

Observational Data from Planetary Science

Beyond Earthly laboratories, clues about abiogenesis come from space and Earth’s geological record. Meteorites, comets, and planetary missions have revealed that the building blocks of life are widespread in the cosmos. A landmark discovery in 2022 was that all five nucleobases (A, C, G, T, U) were found in carbon-rich meteorites that fell to Earth. Previously, only adenine and guanine had been clearly identified in meteorites; the new analysis, using sensitive techniques, detected the “missing” pyrimidines cytosine and thymine as well. The concentrations were low, but their presence supports the idea that some prebiotic material was delivered to the early Earth from space. An accompanying lab study simulated cosmic conditions (UV irradiation of simple ices) and produced the same nucleobases, indicating they can form in interstellar environments. In 2019, scientists also confirmed the presence of extraterrestrial sugars in meteorites, including ribose – the sugar component of RNA. Isotopic analysis showed these sugars were likely formed by chemical processes in asteroids (such as the formose reaction, which produces sugars from formaldehyde) rather than being contamination. This was the first direct evidence that biologically important sugars rain down from space, raising the possibility that the early Earth’s inventory of organics was “seeded” with some ready-made ingredients. To be clear, this is not the same as panspermia (the idea that life itself came from space, which we are excluding here), but it suggests a hybrid origin where terrestrial and extraterrestrial chemistry both contributed to life’s precursor molecules. If meteorites delivered a supply of amino acids, nucleobases, and amphiphiles (many meteorites are rich in fatty acids too), that could have jump-started the emergence of life’s building blocks on Earth.

Within the Solar System, we also see potentially analogous environments to Earth’s early days. NASA’s Cassini mission detected organic compounds, including some complex macromolecules, in the water plumes of Enceladus (a moon of Saturn with a subsurface ocean and likely hydrothermal vents on its seafloor). The presence of H₂, CO₂, and organics in those plumes is remarkably reminiscent of the conditions hypothesized for Earth’s vent-based origin. While no actual life was found, the chemistry hints that Enceladus has the ingredients and energy sources for abiogenesis – essentially a natural experiment occurring (or that could have occurred) beyond Earth. Mars rovers have also found organic molecules (like simple chlorinated organics in ancient rocks and methane in the atmosphere that varies seasonally).

Mars in its youth had liquid water and volcanic activity, so it’s plausible similar prebiotic chemistry took place there. Though no direct evidence of past life on Mars has been confirmed, the fact that organics persist in Martian sediments for billions of years suggests that if life had started, some molecular fossils might eventually be uncovered.

Finally, Earth’s own geological record, sparse as it is for >3.5 Ga events, offers hints, isotopic signatures of carbon in 3.8 Ga rocks from Greenland have been interpreted by some as evidence of life’s metabolism (a preference for lighter carbon isotopes). And as mentioned, filamentous structures in 3.7–4.0 Ga iron-rich formations have been controversially claimed as microfossils.

Further, a team, led by Hamed Gamaleldien, a geochemist at Khalifa University who presented the results at the 2024 conference of the European Geosciences Union, has suggested that Carbon found in 4.0Ga zircon crystals from Australia not only hint at life, but that Earth had land and freshwater at least 500 million years earlier than previously thought. Work has been ongoing for more than 2 decades now on the zircon crystals extracted from the Jack Hills area of Australia.

If even a fraction of these claims are valid, it means life was present and possibly already metabolically sophisticated very soon after Earth stabilised, consistent with a rapid emergence scenario.

In summary, experimental and observational evidence accumulated in the last decade has made the origin of life seem a bit less mysterious, though still far from fully understood. We now have plausible chemical routes for making all the molecular “letters” of biology under realistic conditions. We have seen simple systems that mimic key processes, such as replication, metabolism, compartmentalisation, in the lab. We’ve learned that many of the necessary molecules form naturally in the universe and were delivered to early Earth during its formation, not requiring material to be brought in my impacting bodies. These findings across disciplines mutually reinforce each other, painting an increasingly coherent picture of how abiogenesis could have happened.

Transition to Protocells

A crucial milestone on the road from chemistry to biology is the formation of the first protocells, entities that are precursors to true cells, having a boundary and internal environment but simpler in composition and function. A protocell, in essence, is a package that contains some self-perpetuating chemistry, such as replicating molecules or metabolic reactions. The emergence of protocells marks the point where different threads of prebiotic evolution, genetic molecules, catalytic networks, membranes etc, come together into an integrated system.

In the follow section, we explore how simple molecules might assemble into protocells, and what recent research says about the requirements for this transition and the self-replication, compartmentalisation, and chemical evolution within those compartments.

Self-Assembly of Compartments

One striking aspect of modern cell components is that many will spontaneously assemble given the right conditions, for example, lipid bilayers form on their own in water, and proteins or RNAs can self-organise into complexes. The simplest protocells were likely based on amphiphile membranes, such as fatty acid vesicles, because such structures form readily and can grow and divide through physical processes. As discussed in the Lipid World section, fatty acid vesicles provide an ideal model of a protocell boundary, they are semi-permeable, allowing small nutrient molecules to enter, they can encapsulate genetic or metabolic molecules, and they can undergo cycles of growth and division.

Laboratory studies have demonstrated the plausibility of each of these steps. For instance, a model protocell can be fed with additional fatty acids, simulating lipid synthesis, the result is the membrane incorporates the new lipids and expands. If the vesicle becomes oversized or is subjected to shear forces, it will split into two smaller vesicles, effectively “reproducing.” Crucially, anything inside the vesicle , e.g. RNA strands, gets partitioned between the daughter vesicles. In this way, an encapsulated replicator can benefit from being inside a compartment that multiplies. Joyce and Szostak succinctly defined a protocell as a compartment that hosts the replication of a genetic molecule and local accumulation of its catalysts/products (Ref. Link). This local containment is vital – without it, any useful product (like a self-replicating RNA or an enzyme) would diffuse away and be diluted in the ocean, losing any competitive edge. The protocell provides localised selection; if an RNA makes itself replicate faster, that happens inside its vesicle, making that vesicle grow or reproduce faster than others. Natural selection can thus start acting at the protocell level (Ref. Link).

Integration of Replicators and Compartments

Recent experiments have managed to reconstitute partial “protocell systems” that integrate replication and compartment growth. In one notable study (Szostak’s group, 2013), an RNA enzyme that can ligate (join) RNA fragments was encapsulated inside fatty-acid vesicles along with its substrate. The RNA enzyme was able to perform its reaction inside the vesicle, and when vesicles were fed with fresh substrate from outside, the substrate permeated in, and the reaction continued, a primitive metabolism inside a lipid container.

Furthermore, when new fatty acids were added, vesicles grew and divided, distributing the RNA enzyme to progeny. This demonstrated a coupling of genetic and membrane reproduction; the first time a cycle of RNA-catalysed reaction concurrent with protocell growth and division had been achieved. Although the RNA in this case wasn’t fully self-replicating, it showed that the environment inside a vesicle does not prevent complex RNA chemistry; in fact, it can keep reactants together and even provide rudimentary homeostasis (the membrane can buffer interior conditions to some extent).

Another important element is membrane permeability. Early protocells likely had leaky membranes, especially if made of simple fatty acids rather than today’s phospholipids, which is actually beneficial. A leaky membrane allows nutrients, like activated nucleotides or amino acids, to enter from the environment and wastes to leave, without the need for sophisticated transport proteins.

Research in 2018 demonstrated that membranes composed of certain fatty acid mixtures are permeable to charged molecules like nucleotides, meaning an RNA strand inside a protocell could still get the raw materials, the nucleotides, it needs to grow or copy itself, as long as those are supplied outside. However, once the nucleotide is polymerised into RNA, the large strand cannot leak out easily, effectively trapping the genetic polymers inside. This creates a simple but effective one-way gate, building blocks in, polymers stay in. Such mechanisms would have helped concentrate life’s early macromolecules within protocells.

Alternative Protocell Models

While fatty acid vesicles are the most studied protocell model, other types of compartments have been proposed and tested. One is coacervate microdroplets, which are membraneless droplets formed by phase separation of polymers (like proteins and nucleic acids) in water – rather like how oil droplets separate from vinegar. Coacervates can concentrate a variety of molecules and create an isolated internal environment. In the past few years, researchers have explored coacervates as potential protocells because they form easily when oppositely charged polymers are mixed, and they can incorporate primitive catalysts. For example, a 2023 study created coacervate droplets from simple peptides and the small molecule ferricyanide. These droplets were shown to catalyse chemical reactions internally: the ferricyanide provided an oxidizing power that drove the formation of amide bonds (essentially linking amino acids into peptides) right inside the coacervate (Ref. Link). Notably, the reaction was selective , certain amino acids were incorporated into peptides more readily than others, depending on their interactions with the coacervate matrix (Ref. Link).

This hints that membraneless protocells could foster specific chemistries and possibly a rudimentary form of selection (some droplets might produce useful peptides that enhance stability or functionality of that droplet). Coacervates are interesting because they resemble the “organic soup droplets” that Alexander Oparin hypothesized in the 1920s as precursors to cells. Modern techniques have now validated that idea by showing coacervate protocells can concentrate nucleotides, catalyse reactions, and even undergo fusion and fission cycles. One drawback is that coacervates tend to be less physically stable than lipid vesicles (they can disperse if diluted), but they could have served as intermediate structures or worked in tandem with membrane-bound protocells.

Another model involves mineral “armoured” bubbles – experiments have shown that gas bubbles rising through volcanic mud can become coated by a layer of silica or metal hydroxides, forming a kind of inorganic hollow sphere. These could encapsulate organics and create stable compartments (Harvard researchers in 2011 demonstrated “clay-armoured bubbles” that persist and could have acted as protocell scaffolds (Ref. Link). Such hybrid structures, mineral shell with organic interior, might have been especially relevant at geothermal pools or hot springs on the early Earth.

Chemical Evolution Within Protocells

Once a protocell assembles, the next step is for its internal contents to undergo evolution, i.e. for information bearing molecules to mutate and propagate improved functions, and for the system as a whole to get more complex. For an RNA containing protocell, we imagine a sequence of events but initially a single RNA replicates inside a vesicle. If a mutation makes a copy replicate faster, that RNA will dominate inside. If a mutation causes an RNA to produce a useful catalyst (say, a ribozyme that synthesizes more membrane molecules or improves nucleotide import), then the protocell containing that ribozyme will grow or replicate faster than others, thus spreading that ribozyme gene to the next generation of protocells. In this way, Darwinian evolution kicks in at the protocell level (Ref. Link).

Recent theoretical models have examined the dynamics of such systems, confirming that a coupled replication + vesicle system can evolve complexity that neither part could alone. One crucial finding from simulations is that there’s a balance to be maintained: the replication of genetic material and the growth of the container must be synchronized to some degree. If RNA replicates much faster than the vesicle grows, you get too much RNA inside, which can, paradoxically, hinder function (overcrowding or causing the vesicle to burst). If the vesicle grows faster than RNA replicates, you dilute the RNA and lose function. So the most successful protocells likely were those where membrane growth and genome replication were in harmony – a selective pressure that perhaps led to early regulation mechanisms (for example, an RNA that enzymatically synthesizes membrane lipids would inherently link genome replication to membrane production).

Experimentally, we are beginning to see inklings of evolution in action in artificial protocell populations. In 2016, a team created populations of lipid vesicles that encapsulated RNA ribozymes and set them through a serial transfer process, analogous to serial culture. They observed variations in vesicle growth rates depending on which ribozymes were inside, and after several cycles, the composition of the ribozymes shifted, hinting that those conferring faster growth were becoming enriched. While not a full demonstration of open-ended evolution, it’s a proof-of-concept that selection can occur at the protocell level. Another experiment in 2021 showed that if you have two types of protocells, one with a metabolic enzyme that produces a fatty acid and one without, the enzyme-containing protocells will secrete fatty acids that can be absorbed by both types (a kind of primitive “public good”). However, if the enzyme is too beneficial, protocells lacking it can freeload and outnumber the producers. This scenario mimics a social evolution problem; remarkably, it was found that compartmentalization can prevent freeloading because the producers tend to retain enough advantage locally. These nuanced studies are bringing evolutionary theory into the origin-of-life realm, demonstrating what conditions favour the stability of a protocell that contains collaborative molecules versus being undermined by selfish elements, like parasites that replicate but don’t contribute to membrane growth.

In short, the transition to protocells is about integration and encapsulation. All the pieces, nucleic acids, peptides, lipids, minerals, could have existed in the environment, but life began when they came together into bounded units that could replicate and evolve as units. Over the last decade, research has shown that this integration is chemically feasible: fatty acids do form vesicles that house replication; simple metabolic cycles can occur inside compartments; and those compartments can proliferate. Protocells provide the solution to the paradox of needing lots of molecular complexity all at once; they allow incremental assembly of complexity in one locale, protected from being lost to the wider environment. They are the platform on which further biological innovation could build. Once a protocell can reliably copy its information polymer and reproduce itself, many consider that a form of life, albeit primitive, has emerged. The subsequent steps would then transform these “temporary” protocells into the more permanent and efficient cells of LUCA’s era.

From Protocells to LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor)

If protocells were the first stepping stones to life, at some point they had to evolve into something we could recognise as a true cell, complete with the molecular machinery shared by all modern life. Biologists often refer to the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA) as the progenitor of all extant life forms, essentially, the final stage of early evolution before the divergence of Bacteria, Archaea and later Eukarya. LUCA is not thought to be the absolute first life, but rather the survivor, or communal lineage, of an earlier diversity of primitive organisms. Reconstructing what LUCA was like, and how the transition from simple protocells to LUCA occurred, is a fascinating challenge that blends biochemistry, genomics, and evolutionary theory.

Features of LUCA

Recent comparative genomics studies have attempted to infer LUCA’s gene set by finding genes common to all domains of life and using phylogenetic methods to determine which are truly ancestral. In 2016, a landmark study by Weiss et al. analysed millions of protein sequences across bacteria and archaea, identifying 355 gene families that likely trace back to LUCA (Ref. Link). From these, they deduced a portrait of LUCA’s biology. LUCA appears to have been a microbe, a single-celled organism, that already had a fairly advanced toolkit, it was anaerobic, living in the absence of oxygen, H₂ dependent, using hydrogen gas as an energy source, and CO₂ fixing, able to assimilate carbon from CO₂, likely via the acetyl CoA pathway (Ref. Link). It was also N₂-fixing, meaning it could convert atmospheric nitrogen to ammonia , a complex metabolic trick found in some bacteria and archaea today (Ref. Link). LUCA was thermophilic (heat-loving), hinting it lived in a hot environment, possibly near hydrothermal vents. Its enzymes were riddled with Fe–S clusters and used metal cofactors like molybdenum, selenium, and coenzyme factors, e.g., flavins, coenzyme A) (Ref. Link). Strikingly, LUCA’s gene set implies it had the enzymatic core of a primitive metabolic network, including parts of the Wood–Ljungdahl (acetyl-CoA) pathway for carbon fixation (Ref. Link). This strongly supports an autotrophic origin of life in a hydrothermal setting, since those metabolisms are typical of vent microbes today. LUCA also had a genetic code and the machinery for protein synthesis: the study found evidence that LUCA’s genetic code required modified nucleosides (a sign that translation and tRNA modifications were in place) (Ref. Link). In other words, LUCA almost certainly had DNA, RNA, and ribosomes to make proteins. It may not have been a fully modern cell, but it was not too far off – lacking perhaps some of the bells and whistles of later cells (like a full lipid biosynthesis pathway for complex membranes, or sophisticated regulatory proteins).

How Did LUCA Emerge?

The journey from a simple RNA-and-fatty-acid protocell to something as complex as LUCA was probably incremental and involved many intermediary forms. One hypothesis is an “RNA/protein world” existed between the RNA World and LUCA. In an RNA World, proteins are absent; by LUCA’s time, proteins (made of 20 amino acids) were the main catalysts and structural components, and DNA had likely taken over as the stable genetic material. The intermediate stage might have featured the co-evolution of RNA and peptides – perhaps short peptides started assisting RNA replication (acting as primitive polymerase cofactors or stabilizing RNA structures), while RNA guided peptide formation (early ribosome precursors). Eventually, the ribosome evolved – a key event in which an RNA machine began synthesizing proteins using the genetic code. The ribosome is a ribozyme (its peptidyl transferase centre is RNA) but uses proteins for support, which is a nice demonstration of RNA and proteins working together. The origin of the genetic code itself remains an open question, but one popular theory is that it started very small (maybe encoding just a few amino acids) and expanded. Experiments have shown that some amino acids can enhance the polymerization of specific RNA sequences (perhaps a hint to how certain codons got assigned to certain amino acids – via chemical affinities in an RNA/peptide world).

Another important transition is from whatever membrane protocells LUCA’s ancestors had to the more complex membranes of LUCA. Modern Bacteria and Archaea have membranes made of phospholipids with embedded proteins, and interestingly, their lipid compositions differ (implying that the last common ancestor of Bacteria and Archaea might have had a simpler membrane, possibly just a fatty acid membrane like protocells). There is a hypothesis that LUCA had a “leaky” lipid membrane and lived in an environment where it didn’t need sophisticated pumps – consistent with a vent setting where the environment provided a constant chemical gradient. Only when life diversified into different environments did the two lineages develop tighter membranes with their own distinct lipids and better transport control.

Incorporation of DNA

LUCA likely already had DNA as the genetic material (given that all life uses DNA, and it’s more stable than RNA for long genomes). But DNA is thought to be a later innovation – the RNA world organisms probably managed with RNA genomes initially. How did DNA appear? The common view is that after the evolution of ribozymes and proteins, one of the protein enzymes (perhaps an RNA-templated RNA polymerase) mutated to create a reverse transcriptase, copying RNA into DNA (Ref. Link). Indeed, the Joyce & Szostak review notes that an RNA polymerase ribozyme can act as a reverse transcriptase under some conditions, suggesting an RNA-based life could produce DNA as a byproduct. Once DNA was around, it would be favoured for information storage due to its higher chemical stability and easier repair. So early life invented ribonucleotide reductase (to convert RNA building blocks to DNA building blocks) and DNA polymerase, and soon the main genome became DNA while RNA transitioned to intermediary roles (messenger RNA, tRNA, etc.). The retention of RNA in so many central roles (ATP, NADH, coenzymes, ribosome, etc.) is a relic of its once-dominant status.

Metabolic Consolidation

As protocells evolved toward LUCA, their once purely geochemical energy sources may have been supplemented or replaced by biological ones. For example, early protocells in vents might have relied on natural H₂ gradients and mineral catalysts to drive carbon fixation. Over time, enzymes, like hydrogenases, and carbon-fixation enzymes would develop, allowing organisms to more efficiently harness H₂ and CO₂ on their own, though interestingly, LUCA’s inferred metabolism is still tied to H₂ and CO₂, indicating nature stuck with those substrates. The emergence of pathways like glycolysis or the TCA cycle might have come later, but core bits could be older. Some theorists propose that the reverse TCA cycle, which is a carbon-fixing cycle, could have been operating before LUCA with mineral catalysts, and enzymes later took over the same cycle. Eventually, life would innovate to exploit new energy sources, such as sunlight. However, the consensus is that photosynthesis evolved after LUCA, as LUCA seems to have been non-photosynthetic, there’s no evidence it had the genes for pigments or light-driven pumps) (Ref. Link). This makes sense, early Earth life likely inhabited rich chemical environments, such as previous discussed vents, and only later did some organisms venture into sunlit waters, developing photosynthesis, perhaps as early as 3.5Ga or later, given the fossil record of cyanobacteria like cells.

The “Grey Zone” of Early Evolution

There might have been a transitional period with quasi-living systems – more complex than a simple protocell, but not yet with the full suite of LUCA. Some researchers speak of a progenote stage, where the linkage between genotype and phenotype was still loose (meaning the genetic material wasn’t fully dictating all traits, perhaps because the translation apparatus was still low-fidelity or incomplete). In such a scenario, early cells might have had a lot of horizontal gene transfer and modular evolution, making the concept of a single lineage fuzzy. This could partly explain why certain cellular features (like the exact components of the ribosome or membrane lipids) differ between major domains of life – those might have been finalized only after different lineages of early cells had already branched off. There’s a view that the tree of life, near its root, might have been more of a network with rampant gene exchange, only later solidifying into distinct branches. The idea of a “LUCA community” is sometimes raised, where a community of organisms shared genetic innovations until a point where separate vertical lineages became dominant.

Dating LUCA

A surprising recent result came from molecular clock analyses by Daviditt et al. and Moody et al. (2023–2024), which tried to put a date on LUCA (Ref. Link). By calibrating gene sequence differences with geological constraints (like known fossil ages and gene duplications), one study estimated LUCA lived as much as 4.2 billion years ago (Ref. Link). This is extremely early, Earth is only ~4.54Ga and many believe that it likely only became habitable between 4.1Ga to about 4.3Ga when the crust had cooled sufficiently. A LUCA at 4.2 Ga implies that the entire process from first life to a quite advanced cell happened in perhaps 100 million years or less. While this estimate has uncertainties, it aligns with geological hints of life by ~3.8Ga – 4.1Ga and underscores how quickly evolution can move once the threshold of Darwinian selection is crossed. If true, it means primitive life could have appeared almost as soon as conditions allowed and then rapidly evolved to the LUCA stage. Some have even speculated that life might have started during the tail end of Earth’s accretion, in localised niches that survived big impacts, but solid evidence is lacking. In any case, the path from protocells to LUCA likely involved intense evolutionary pressures, each improvement, such as a better catalyst, a more stable genome, or an energy-capturing mechanism, opened new frontiers and enabled more improvements in a positive feedback loop.

By the time of LUCA, the world of life had the core processes we recognise, DNA replication, with an RNA primer and DNA polymerase, RNA transcription, protein translation via ribosomes, and a suite of enzymes for basic metabolism. LUCA might have already inhabited a hydrothermal vent, feeding on H₂ and CO₂, or possibly drifted to other environments if it had a robust membrane. From LUCA, life split into different lineages, which then evolved astonishing diversity, but studying LUCA gives us a glimpse of life’s starting toolkit. It tells us that biochemistry as we know it – including the genetic code and ATP-based energy, was established very early. The journey from simple chemical beginnings to LUCA illustrates increasing integration, initially separate systems, like genetic replication vs. metabolic energy production, became linked in one organism. At some point, biology took the reins from geology, enzymes replaced mineral catalysts, lipid membranes replaced rock pores, DNA took over information from RNA. The exact sequence of these handoffs is still to be unravelled, but each represents a major evolutionary milestone on the road to modern life.

Recent Challenges and Open Questions

Despite significant advances, the origin of life remains a field with many unanswered questions and active debates. Here we highlight some of the critical challenges and open issues that researchers are currently grappling with:

- Bridging Multiple Models – The “Chicken-and-Egg” Problem

One fundamental challenge is integrating the various models, RNA world, metabolism-first, lipid-first, into a coherent story. Each model by itself explains certain aspects but also has gaps that often would be filled by the others. For instance, an RNA world needs a supply of nutrients, a metabolism, and a stable environment, compartmentalisation, to succeed.

A metabolism first scenario needs some way to transmit improvements, information, to actually evolve into biology. How did these components come together? Did metabolism in vents create the building blocks that enabled an RNA world within lipid vesicles, effectively a sequential origin – metabolism → RNA → cells? Or did they emerge in parallel in a unified setting, such as replicating RNA + lipid vesicles at a vent? This question of the convergence of pathways is still wide open to debate. There’s growing thought that the old dichotomies, “RNA vs metabolism first”, are false, life likely arose from interactions of molecules that later became genes, catalysts, and membranes all at once (Ref. Link).

However, experimentally demonstrating a path that links them seamlessly is a work in progress. Researchers are now designing experiments that mix replicating molecules with metabolic cycles inside compartments to see if they can co-evolve. This is essentially trying to create a protocell that can evolve in the lab, a grand challenge that would be a huge breakthrough if achieved.

- Origin of the Genetic Code and Translation

Perhaps the most staggering leap in complexity during abiogenesis is the invention of the translation system, converting nucleic acid sequences into proteins. The ribosome is an incredibly complex molecular machine, and the genetic code, mapping 64 codons to 20 amino acids, seems arbitrary yet universal. How could something so intricate evolve from simpler components?

One line of thought is that early peptides were very short and perhaps even non-coded, for example, certain amino acids might have chemically coupled with specific RNA sequences, some codons show affinities for the amino acids they code, hinting at a stereochemical origin of the code. Experiments have shown that random peptides as short as 5–6 amino acids can have useful activities, like binding a metal or stabilising an RNA fold, so it’s plausible that an RNA world began to recruit such short peptides, maybe initially synthesised by simple chemical means or by ribozymes without a coded system.

Gradually, an encoding mechanism could arise, perhaps initially only a few amino acids were encoded by a rudimentary ribosome, and the code expanded stepwise. However, this is largely theoretical. We have little experimental insight into prototypical translation systems or how a ribosome precursor might function. It remains an open question how the specific set of amino acids was chosen and how the code became fixed, for example, why the code is nearly universal, was LUCA’s code already optimal or were there multiple codes that one outcompeted?

Some progress has been made in minimalist ribosome research, like fragmenting the ribosomal RNA and seeing smaller subunits that still retain some function, but the origin of translation is still considered one of the hardest issues in origins research.

- Homochirality

Life uses molecules of specific chirality, left-handed amino acids, right-handed sugars, but abiotic chemistry typically produces racemic, equal left/right mix, mixtures. How did biology’s homochirality emerge? This is an old puzzle and still debated. Various hypotheses exist, chiral selection could have come from physical asymmetric influences, like polarised light or mineral surfaces that favour one chirality, or it could be a frozen accident (one lineage of molecules happened to become slightly enriched in one hand and then took over). In the last decade, experiments showed that relatively small chiral biases can be amplified by crystallization processes or autocatalysis, e.g., the Soai reaction is a famous autocatalytic reaction that can produce an extreme enantiomeric excess from a tiny initial imbalance. One study found that sugar molecules in meteorites showed enantiomeric excesses favouring the same handedness as life’s sugars (Ref. Link), potentially due to circularly polarised UV light in space.

This suggests that some bias might have been delivered to Earth. Still, converting that into a fully homochiral biology is tricky. Some proposals suggest early enzymes or ribozymes would work more efficiently if substrates were of one hand, pushing the system towards purifying one chirality. This question ties into another challenge, building large, structured polymers, like RNA or proteins, is much easier if all subunits have the same chirality, as mixed chirality tends to prevent proper folding or double helix formation. Thus, life likely had to choose one to get stable enzymes and genomes. The exact sequence of how that choice was made remains unresolved and widely debated.

- Geological Uncertainties – Environment of Origin

We still don’t know for sure where on Earth life originated. Each proposed environment (deep-sea vents, geothermal ponds, icy oceans, etc.) has advantages and disadvantages. For example, hydrothermal vents provide energy and catalysts but could also be too hot in places (risking molecule degradation) and might dilute organics into the vast ocean. Land-based pools offer wet-dry cycling (good for polymerization) but might lack continuous energy or be subject to UV radiation destructive to some molecules. Recent evidence from the geology of early Earth suggests there were indeed subaerial hot springs around 3.5 Ga (with geyserite deposits similar to those in Yellowstone), giving some support to the idea life could have started on land. Conversely, the discovery of really old probable vent deposits (as mentioned, ~3.77 Ga with possible fossils) supports the marine vent scenario. It’s an open question which (if either) was the true cradle of life. Some have suggested a hybrid: perhaps basic building blocks formed in the atmosphere or shallow ponds and were washed into the ocean, where vents then took over to assemble them into living systems. We may find more answers in the geological record with new techniques; for instance, scientists are looking at isotope ratios of multiple elements (S, N, Fe) in ancient rocks for signatures of biological cycles. So far, evidence points to life being present by ~3.7 Ga, but where it began before that is anyone’s guess.

- Time Scale and Likelihood

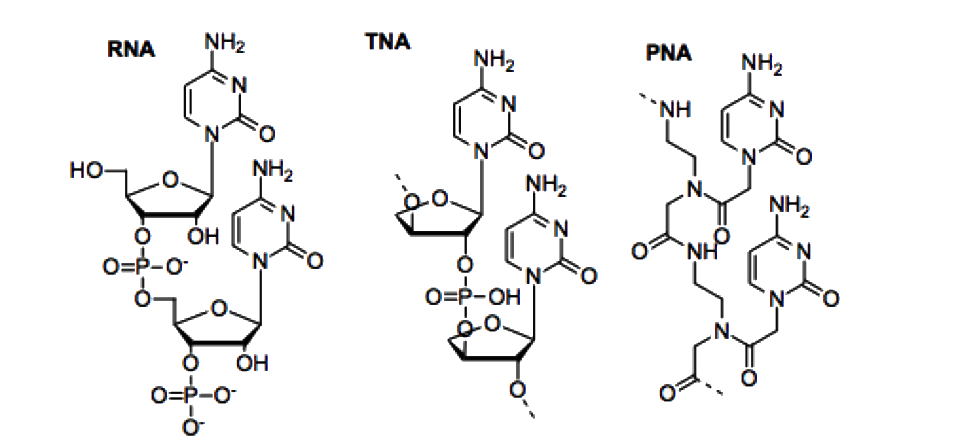

Was the origin of life an extremely rare event or something that would almost inevitably happen given Earth-like conditions? This is an open question with profound implications (including for the search for extraterrestrial life). The rapid appearance of life on Earth suggests it might not be exceedingly difficult, but that could be a biased view (we only have one data point, and if life hadn’t emerged here, we wouldn’t be around to note it). Some researchers argue that certain steps in abiogenesis (like the emergence of a self-replicating polymer) might be statistically improbable, but given the vast number of trials (e.g., countless pools, vents, and micropores over millions of years), even low-probability events could occur. Others point out that we still have no synthetic example of life from scratch – meaning maybe it’s indeed a highly constrained, rare outcome. This ties into an open question about contingency: if we replayed Earth’s early history, would life always appear, and would it always use DNA/RNA/proteins, or could very different chemistries result? We know alternative chemistries, like PNA or TNA instead of RNA, or different amino acids, are possible in principle, but life settled on the ones we have. Were those simply the most robust options, or just one lucky happenstance?

- Missing Pieces and Experimental Gaps

On the experimental front, a challenge is that we have achieved each step of the process in isolation, monomer formation, polymerisation, compartmentalisation, etc, but not all together in one continuous experiment.

How do we go from raw inorganic ingredients to a self-reproducing protocell in one setup? That is a holy grail experiment. It may require a very specific sequence of environmental changes, for example, volcanic gases spark into organics, organics collect in ponds, ponds dry out to make polymers, it rains and washes polymers into the ocean, they find a vent and get encapsulated in a vesicle.

Simulating even a simplified version of this chain in the lab is daunting. Researchers are building “origin-of-life reactors” that try to cycle through various conditions (wet/dry, hot/cold, light/dark) to see if complexity accumulates over time. So far, no experiment has spontaneously generated something one could call alive or even a self-sustaining evolving system. We might be missing some crucial intermediate or condition. As Leslie Orgel famously said, “there is no known chemical law that says life had to emerge” – implying we might have to discover some new chemistry that life exploited (Ref. Link).

Indeed, Orgel and others have pointed out the challenge that many origin scenarios require a sequence of specific events, which when multiplied together seem highly improbable.

One open question is whether there was some kind of inevitability provided by non-equilibrium conditions, for example, did the thermodynamics of Earth, with lots of free energy sources, make the emergence of order (life) more probable due to principles of dissipative systems and determinism?

Physicists like Jeremy England have speculated that under a flux of energy, matter tends to self-organise in ways that dissipate energy more effectively, and life is an outgrowth of that principle. This is still unproven, but it’s a fascinating idea bridging physics and biology, and it remains to be seen if such theoretical frameworks can predict or explain the origin of life.

- Extraterrestrial Validations

Finally, one way to resolve some origin of life questions is to find independent examples of life. If we find life, even microbial, that started on Mars, Europa, Venus, Ceres, Titan Enceladus, or beyond, and if it shares fundamental biochemistry with us, or doesn’t, it will be illuminating for the whole field. For example, if Martian life also uses DNA/RNA and amino acids, it might imply either panspermia or that those molecules are a deterministic outcome of chemistry. If it uses a different genetic system, it could show there are multiple solutions to life’s origin. NASA and other agencies are keen on astrobiology missions for this reason. Until we have that data, we are reverse engineering one occurrence of life, which may be misleading and unhelpful in the overall picture of life’s origins.

So, the question “Are we alone?” ties in – it’s partly a question of how likely abiogenesis is. At present, we can’t estimate that likelihood because we don’t fully understand the process. It remains one of the biggest open questions in science.

In summary, while our understanding of abiogenesis has grown, numerous challenges remain. We have pieces of the puzzle but not the full picture of how they fit together. The origin of life likely involved a web of interactions, and unravelling that web requires interdisciplinary efforts and perhaps some novel thinking that breaks the constraints of how we imagine early processes. Each breakthrough, whether it’s a new catalytic route, a synthetic cell that can evolve, or a fossil finding, helps chip away at these questions, but for now the origin of life continues to invite both wonder and scepticism in roughly equal measure.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Research into the origin of life has made remarkable strides in the past decade, bringing us closer to demystifying how inert matter gave rise to living systems. We now have plausible narratives for many individual steps, simple inorganic molecules can produce life’s building blocks, that those building blocks can assemble into polymers, that polymers and lipids can form protocell structures, and protocells, under the right conditions, can exhibit rudimentary life like behaviours.

The classical boundaries between competing theories are blurring, as scientists recognise that life’s origin likely required multiple ingredients acting in concert, genetic molecules, metabolic cycles, membranes, and environmental drivers all playing a part.

This holistic view is guiding current research, which is increasingly interdisciplinary. Chemists, biologists, geologists, physicists and astronomers are collaborating to reconstruct a continuous “pathway to life” that is chemically and geologically credible.

One key takeaway from recent progress is that many aspects of abiogenesis are not as improbable as once thought. Pathways that seemed chemically implausible, like making RNA’s nucleotides from scratch, have turned out to be achievable under surprisingly simple conditions.

Likewise, environments thought unfavourable, alkaline hot vents for membranes, or high UV for organics, have been shown to have workarounds or even advantages. This injects optimism that we might, in the not too distant future, succeed in creating a self-replicating, evolving protocell in the lab, effectively “replaying” abiogenesis in a simplified form. Achieving that would be a milestone comparable to synthesising life, and it would provide a definitive proof of concept that abiogenesis is a natural consequence of chemistry under the right conditions. (Ref 1 Link) (Ref 2 Link)

In the near term, future research directions include:

- Integrated Proto-Systems

Building systems that combine informational polymers, metabolism, and compartments to see emergent properties. For example, experiments where a synthetic cycle produces an energy-rich compound that an RNA uses to fuel its replication, all inside a vesicle. The goal is to observe selection and evolution in such systems, essentially creating a living chemistry set.

- Novel Chemistries

Exploring alternative nucleic acids (like XNA – Xeno nucleic acids) or peptides that could have preceded standard DNA/RNA/proteins. This could reveal if life had “prototype” molecules that were later replaced by modern ones. Also, looking at the potential of simpler metabolic cycles, maybe two or three step cycles, that could bootstrap larger networks.

- Environmental Simulations

More sophisticated simulations of early Earth environments, perhaps using microfluidic devices to replicate rock pores or gradient systems. This also extends to simulating early Earth atmospheres with updated models, accounting for volcanic gas compositions, early solar radiation, etc, to refine what raw materials were available. Collaboration with geologists to identify specific locales, e.g., impact craters with hydrothermal activity, as hot spots for chemical evolution is another area.

- Astrobiology Missions

As technology permits, missions to Mars (e.g., Mars Sample Return), icy moons (Europa Clipper, Titan’s Dragonfly, etc.), and even extrasolar planet observations will inform origin of life studies. Finding organic chemistry elsewhere, or even primitive life, would hugely influence our theories. If signs of past life are found on Mars, we could compare its biomarkers with Earth’s to infer if it had a separate origin. The detection of complex organics like amino acids on ocean worlds would support the universality of the processes we study in the lab.

- Theoretical Frameworks

There is a push to develop a more formal theory of the origin of life, something that can predict under what conditions a lifelike system will emerge. This might involve applying complexity theory, information theory, or non-equilibrium thermodynamics to biochemical networks. The hope is to move from a purely historical science, explaining how it happened here, to a more general science of “living matter” that could apply anywhere. Efforts like Jeremy England’s hypothesis of dissipative adaptation or Sara Walker’s work on information in chemical networks are examples of trying to frame life’s origin in general physical terms. (Ref. Link)

- LUCA and Beyond

On the bioinformatics side, refining our picture of LUCA and the early evolutionary tree can yield clues to conditions and processes at life’s dawn. If, for example, certain enzymatic cofactors, such as particular metals, are shown to be universally ancient, that flags those metals as important in prebiotic chemistry. Continuing to search for “molecular fossils” – modern biomolecules that might have had different roles in the RNA world, like tRNA, which some think was a replicator before it became an adaptor, can inspire experimental chemists to replicate those functions in the lab.

In concluding, it’s worth emphasising that abiogenesis research is inherently multidisciplinary. The major advances of the last ten years came from blending approaches, organic chemists solving problems posed by biologists, geochemists providing context to chemists, and vice versa. This trend will continue. Origin of life institutes and international collaborations are forming to unite these fields, and new tools, from drone explorations of extreme environments on Earth to advanced spectroscopy of interstellar molecules, are expanding our window of understanding.

While we do not yet have a complete, step-by-step account of how life emerged, the pieces of the puzzle are beginning to fit into a plausible narrative. Life likely arose through a series of emergent transitions, from geochemistry to photochemistry to protocells to true biology, each transition leaving subtle clues we are now learning to detect.

Every discovery, be it a novel ribozyme or a new fossil, adds detail to the grand story of life’s beginning. As science progresses, the gap between non-living and living is steadily narrowing in our experiments, reinforcing the view that abiogenesis is a natural continuum rather than a miraculous leap. The coming years hold the promise of filling in that remaining gap, either by achieving synthetic life in the lab or by finding evidence of life’s spark elsewhere, or, hopefully, both.

Such breakthroughs will not only answer the ancient question of our origins but also deepen our appreciation of life as a cosmic phenomenon, one that might be waiting to be found on other worlds, and one that, on Earth, transformed a barren planet into the vibrant biosphere we inhabit today.

References:

- Ricardo Batista Martins et al., “The Future of Origin of Life Research: Bridging Decades-Old Divisions,” Life 2020 – Discusses the integration of historically opposed origin-of-life theories.pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

- David H. Bailey, “New developments in the origin of life on Earth,” Math Scholar 2024 – Provides a contemporary overview of abiogenesis research and its challenges. mathscholar.org