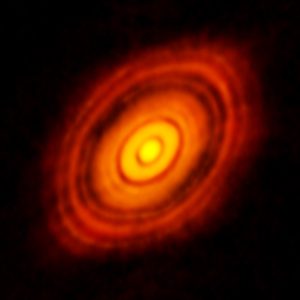

Planet formation is a complex and multi-faceted process occurring within protoplanetary disks that surround young stars. Several theories have been proposed to explain how planets emerge from these disks, with the most widely accepted models being the core accretion model and the gravitational instability model. Recent advancements in observational astronomy and computational modelling have refined our understanding of these processes, leading to new insights into how planets of varying sizes and compositions form.

Core Accretion Model

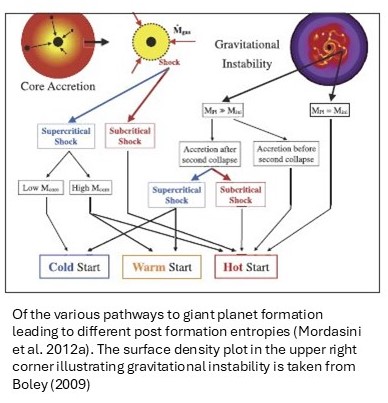

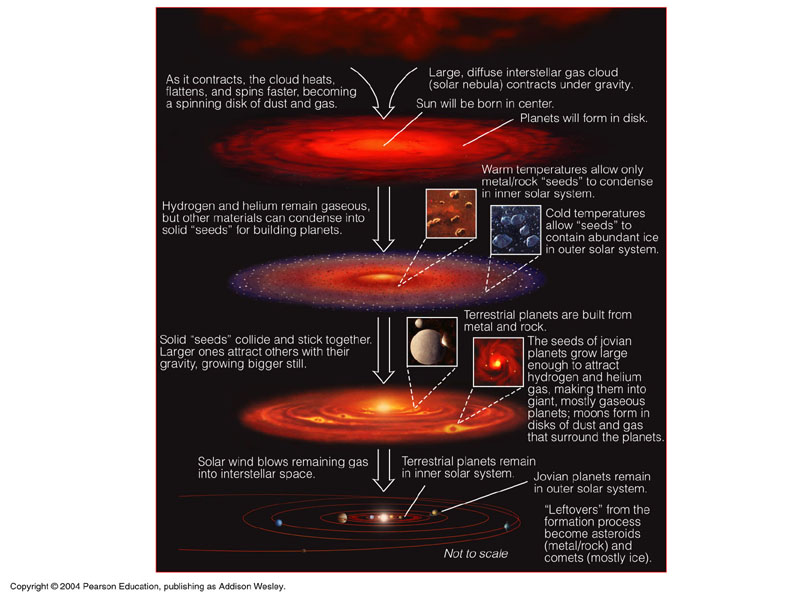

The core accretion model is currently the dominant framework explaining the formation of terrestrial planets and gas giants. In this model, dust and ice particles within a protoplanetary disk collide and coagulate, forming planetesimals—kilometre-sized precursors to planets. These planetesimals further accrete material through collisions and gravitational interactions, forming planetary embryos. Once an embryo reaches a critical mass, typically around 10 Earth masses, it rapidly accumulates surrounding gas, leading to the formation of gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn. Recent studies suggest that pressure bumps within the disk can enhance this process by trapping pebbles and preventing inward drift, leading to efficient planetary core growth (Xu & Wang, 2024).

Gravitational Instability Model

An alternative to core accretion, the gravitational instability model posits that planets can form directly from the fragmentation of a protoplanetary disk. In this scenario, if a region of the disk becomes sufficiently dense and cool, it can collapse under its own gravity to form gas giant planets. This model provides a viable explanation for the existence of massive exoplanets located at large distances from their host stars, where core accretion may be inefficient. However, gravitational instability is likely to be more effective in the early stages of disk evolution when the gas content is still abundant.

Recent Developments and Observations

Several recent studies have introduced refinements to these traditional models. Research on protoplanetary disks suggests that vortices within the disk act as sites of intense dust accumulation, leading to the rapid formation of planetary embryos (Lyra et al., 2024). These findings support the idea that planetesimals can form more quickly than previously thought, possibly resolving issues related to the timescales of planet formation.

Another study highlights the role of transient dust traps in promoting planet formation (Sándor et al., 2024). When turbulence within a disk creates localised pressure maxima, dust can accumulate in these regions, forming planetesimals through streaming instability. This process is particularly significant in explaining the formation of super-Earths and mini-Neptunes, which are commonly observed in exoplanet surveys.

Furthermore, a recent examination of the bouncing barrier—the tendency of dust grains to rebound rather than stick during collisions—suggests that this mechanism may limit the efficiency of dust coagulation and affect planetesimal formation (Dominik & Dullemond, 2023). These findings imply that additional processes, such as turbulence-induced concentration or pebble accretion, may be necessary to explain the rapid emergence of planetesimals.

Implications for Exoplanetary Systems

Theories of planet formation must also account for the diversity of observed exoplanets. The presence of compact multi-planet systems, hot Jupiters, and cold gas giants suggests that migration plays a significant role in shaping planetary architectures. Planets forming in outer regions of a disk may migrate inward due to interactions with the gas, leading to the formation of closely packed planetary systems.

Conclusion

The study of planet formation is continually evolving, with new observational data and theoretical models refining our understanding of this fundamental process. While the core accretion and gravitational instability models remain the leading theories, emerging research on vortices, dust traps, and pressure bumps highlights the complexity of planetary birth. Future observations, particularly from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and upcoming exoplanet surveys, are expected to provide further insights into these processes, ultimately improving our comprehension of how planets, both within and beyond our Solar System, come into existence.